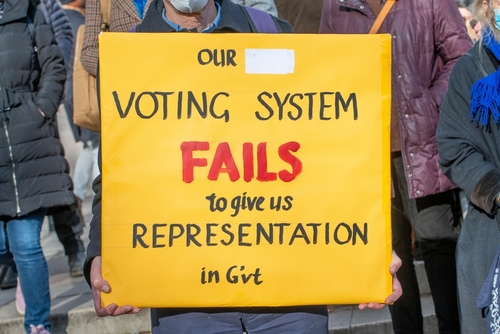

The British electoral system, rooted in First Past the Post (FPTP), is increasingly under scrutiny for failing to reflect the diverse political landscape of the UK. Critics argue it entrenches a two-party dominance, discourages voter turnout, and marginalizes smaller parties. Amid cries of “don’t split the vote” and accusations of enabling Labour or Tory victories, a radical idea is gaining traction: negative voting. This system, where voters can cast a vote against their least favoured candidate, could reinvigorate democracy, boost turnout, and challenge the stranglehold of safe seats.

The “Split Vote” Myth and Political Tribalism

The notion that small parties “split the vote” is a common refrain, particularly from supporters of Reform UK, who argue that parties like UKIP, the Heritage Party, or the Populist Party dilute the anti-Labour vote. Yet, this assumes ideological alignment across these groups, which is far from reality.

Reform UK’s platform—global free trade, Atlanticism, free-market economics, libertarianism, and consumerism—differs sharply from the protectionist, socially conservative, or ecologically focused stances of other parties. To conflate them is to oversimplify the broad spectrum of voter preferences, where “syncretic” mixtures of left and right are more common than in the previous century.

This tribalism extends beyond Reform UK. Tories have long warned that voting for Reform or UKIP risks letting Labour in, while Labour assumes younger voters will back them, only to backtrack on promises like lowering the voting age when polls suggest otherwise. Meanwhile, parties like the Liberal Democrats and Greens rarely lament vote-splitting, instead focusing on their core principles. The obsession with vote-splitting is most acute in winnable constituencies, but in safe seats like Tottenham or Hove, voters can support smaller parties without fear of “wasting” their vote.

The deeper issue is the patronizing assumption that voters must align with a single party to achieve a desired outcome. Politics is not a monolith; it thrives on diversity of thought. Accusing someone of “supporting Labour” for not backing Reform UK (as happens regularly on social media) stifles free will and reduces complex identities to simplistic labels. Many voters are “sick of being told I’m Labour just because I won’t worship at the altar of Faragism.”

The Case for Negative Voting

Negative voting offers a compelling alternative to FPTP. Instead of choosing the “lesser evil,” voters could cast a vote against the candidate or party they most oppose. The candidate with the fewest negative votes would win, ensuring the least unpopular choice prevails. This system could address several flaws in the current setup:

Ending Safe Seats: In constituencies where turnout is low—sometimes as dismal as 27%, as seen in a recent election—negative voting could disrupt entrenched party dominance. Voters in “safe” Labour or Tory seats could use negative votes to challenge long-standing MPs, making their opposition count.

Boosting Turnout: Non-voting is often driven by disillusionment or the absence of appealing candidates. Negative voting would empower abstainers to express their discontent actively. For example, someone who vows never to vote Tory, Labour, Lib Dem, or Green could still participate by voting against their least favored option, rather than abstaining or spoiling their ballot.

Empowering Smaller Parties and Independents: Tactical voting often buries smaller parties, as voters choose Labour or Tories to block the other, despite preferring alternatives. Negative voting could level the playing field. If Labour and Tory voters cancel each other out with negative votes, an independent or smaller party candidate could emerge as the least disliked, giving them a fighting chance.

Ensuring Broader Appeal: FPTP allows candidates to win with less than 50% of the vote, often leaving the majority dissatisfied. Negative voting ensures the winner is the least objectionable to the electorate, aligning more closely with democratic ideals.

Comparing Alternatives: Proportional Representation and AV

Proportional Representation (PR) is often touted as a fairer system, allocating seats based on vote share. However, it has drawbacks: it weakens the constituency-MP link, encourages coalition horse-trading, and can dilute manifesto promises, as seen in the UK’s 2010 Con-Lib coalition. PR also tends to produce hung parliaments, making stable governance challenging.

The Alternative Vote (AV), rejected in the 2011 referendum, allows voters to rank candidates, ensuring the winner secures over 50% of preferences. While an improvement over FPTP, AV still forces voters to rank parties they may detest, perpetuating tactical voting. Negative voting, by contrast, allows voters to express opposition without endorsing anyone, potentially increasing engagement among those who currently abstain.

The Power of Abstention vs. Spoiled Ballots

Abstention and spoiled ballots are often seen as protests, but both are ineffective under the current system. Spoiled ballots are briefly noted by counters, often with derision from major party representatives, and have no impact. Abstention signals rejection of the system but is ignored, as elections proceed regardless of turnout. For example, an MP elected on a 27% turnout lacks a strong mandate, yet the system imposes no consequences.

A radical reform could mandate that elections with turnout below 50% or with more spoiled ballots than votes for candidates be declared void, forcing a re-run with new candidates. This would compel parties to engage voters meaningfully, rather than relying on apathy to secure safe seats.

Another idea that has been touted in tandem with the 50% threshold is NOTA (shortened version of “None of the Above”). The Negivote (Negative Voting), however, is the next best thing in theory as it endorses no-one but still delivers a result. In our current system, a candidate like Sadiq Khan can become London Mayor with 43% of a 41% turnout. Yet there were 12 other candidates to choose from, plus a booklet with all their statements and yet 59% of Londoners didn’t go out and vote for them to get him out because the result was deemed a forgone conclusion. One wonders what the other 59% might have done with a chance to directly vote against Sadiq Khan, rather than being confronted with a 12 options to try to stop him.

A Broken System and a Path Forward

The UK’s electoral system is increasingly seen as a “fraud” by voters who feel their voices are drowned out. With turnout dropping and MPs elected on slim mandates, the case for reform is urgent. Negative voting could re-engage disillusioned voters, challenge safe seats, and give smaller parties a fairer shot. It’s not without flaws—voters might gang up on major parties, leaving fringe candidates as the least disliked—but it would force politicians to appeal to a broader base.

Some voters are forced to be “part of the problem”, voting Tory despite animosity to them in order to block Labour (and vice versa). Negative voting could free voters like these to express their true preferences, whether for a small party or against a major one, without fear of “wasting” their vote. Until such reforms are adopted, the cycle of tactical voting and political apathy will persist, leaving the UK’s democracy stagnant.

Conclusion: Negative voting offers a fresh approach to a stale system. By allowing voters to reject rather than reluctantly endorse, it could restore faith in democracy, boost turnout, and give smaller parties and independents a chance to break through. Combined with penalties for low turnout or excessive spoiled ballots, it could force the political class to take notice. The question is whether the “old guard” will ever allow such a system to take root—or if voters will demand it first.

Author: Russell White, founder and Leader of the Populist Party.

Discussion

No comments yet.